Speed in football PART 2

von

Gastautor

Gepostet am 21.10.2022

This part focuses on possibilities that can help improve the sprint performance.

The largest Improving sprint performance the Mixing of various methods achieved:

1.Sprinting

2.Plyometric training (force development direction = decisive)

- Horizontal = start

- Broad Jumps, Power Skip for Distance, Single Leg Hops

3.Vertical = Top Speed

- Pogo Jumps, Drop Jumps, Continuous Hurdle Jumps

4.Craft training

- Heavy strength training (aka. max. strength training)

- Ballistic training (aka. Power Training) = moderate weight & speed-oriented

The biggest sprint stimulus is sprinting itself!

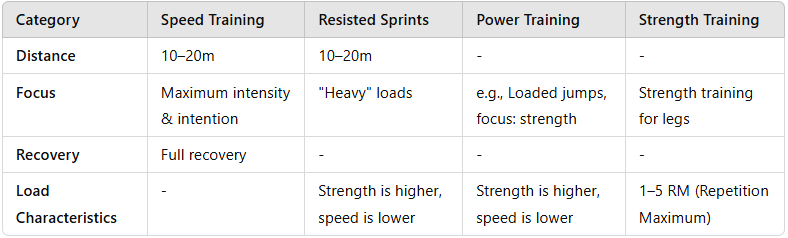

Table 1 Access training

Table 1 Access training

NCM: Non Counter Movement

What??

- First steps of the sprint

Main objectives the start training

- Improving the repulsion force of the first steps of a sprint

- Improving the power development of the first steps of a sprint

How Do I train my appearance?

- The Sprint

- Increase of max. force

- Improving horizontal force development

Why? Do I need a good start in football?

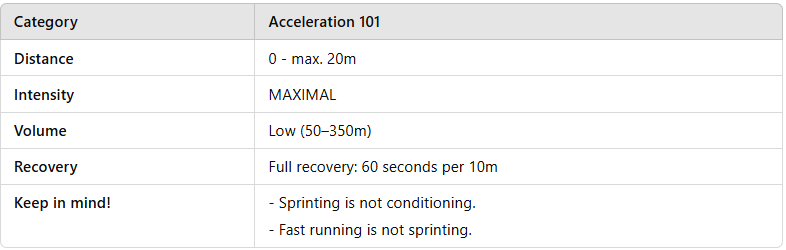

Studies have shown that Sprint stretching a footballer Short are. Footballers often sprint only routes from 0-10 m. It happens that more than 10m are required by a footballer sprinting. Example: During the changeover phase from attack to defense or if there is plenty of space behind the chain.

There are different ways to train the appearance. The most important method is still sprinting itself. You can do what you train! (SAID PRINCIPLE). And if you want to improve your start, you need to sprint short distances with maximum intention & intensity. In summary, you can note the following 3 points you can apply in your start training.

Basic rule: More power should be generated with every single step than many small powerless steps.

- Improvements of maximum horizontal power for entry = Improving horizontal force development + improvement horizontal speed development.

- It is recommended to select exercises that dominance (Force speed curve) are (e.g. maximum power and power training). It can depend on what stage you are in and what you need individually to improve your appearance.

- The training should horizontal & vertical power exercises contain.

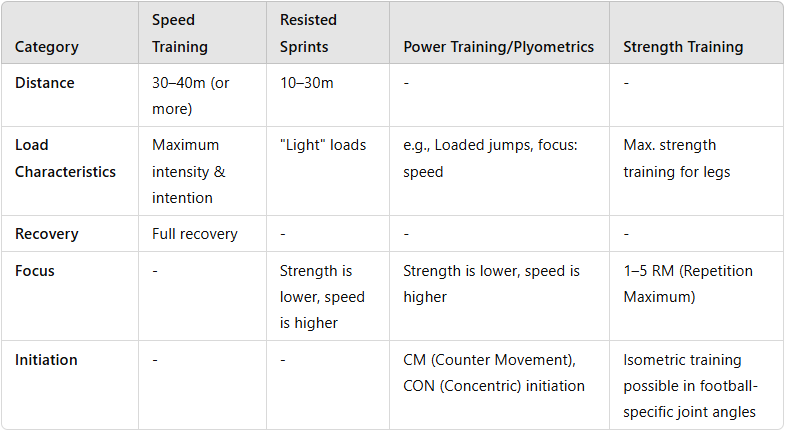

Table 2

Table 2

Table 3 Top Speed Training

Table 3 Top Speed Training

CM: Counter Movement; CON: Continuous

What??

- Maximum final speed

Main objectives the top speed training

- Improving the top speed

- Improving Speed Reserve / Repeated Sprint Ability (RSA)

- Reduction of risk of injury

How do I train Top Speed?

- The Sprint

- Improving vertical force development

Why? do I need top speed in football?

Most sprints in football are submaximal. This means that footballers do not come to the maximum final speed at any sprint. Nevertheless, the training of the top feed is useful.

When the top speed is improved, the submaximum football matches become less strenuous. An investigation has shown that a high speed reserve correlates with improved sprint times.

On the other hand, the maximum sprinting in the top speed range serves Reduction of the risk of injury of the rear thigh muscle (aka. Hamstrings). Hamstring muscle injuries are among the most common contactless injuries in football. Instead of a strict avoidance of maximum sprinting, the maximum sprinting must be implemented in a well planned weekly plan.

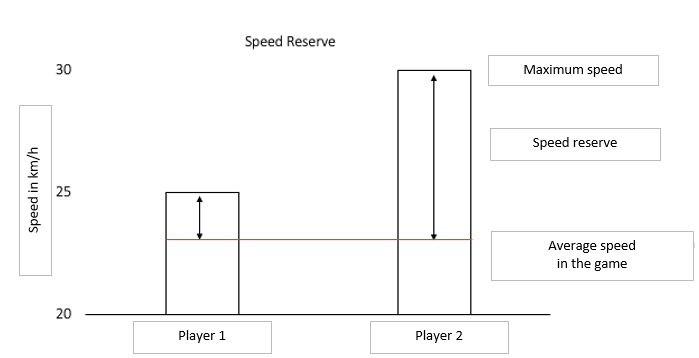

Own illustration Speed Reserve

Own illustration Speed Reserve

Speed reserve

If, for example, the game Average speed of 22 km/h, and we have 2 players (players 1 Top Speed = 25 km/h & players 2 Top Speed = 30 km/h). Which of the two will find the submaximum average game speed for less exhausting? For this reason, the faster player can perform the submaximum performance more often (aka. Repeated Sprint Ability)

Knowledge Sprinten 101

Standing in football fast movements, change of direction and high requirements for the neuromuscular system on the agenda. Rapid action and speed is the quintessence in football. Footballers can reach 85-94% of their maximum speed during the game. Regular sprinting is a suitable method to reduce the risk of injury of the lower extremity and to improve the physical capacity (aka. Performance = better sprint performance). Maximum sprinting is an exercise that generates a very high activation and a very fast contraction speed of the Hamstrings and no force exercise of the world, could replace sprinting.

- The best stimulus for the Hamstrings is sprinting itself.

- Regular sprinting (all 7-10 days Attention: Note the schedule).

- Reduction of Hamstring injuries.

- The most specific basic football action (Verheijen Footbal Action Theory) is sprinting itself.

- Together with an eccentric training for the hamstrings (e.g. with the Nordic Hamstring Exercise exercise), the susceptibility of a hamstring injury can be significantly reduced.

You want to sustainably reduce injuries to your players? Then use our free software for optimal loading and training control:

Here you can find our free software: https://tms.sportsense.at/

With this software you can collect and evaluate data from your players.

About the author Josua Skratek

Josua Skratek is Athletics & Rehatrainer at DSC Arminia Bielefeld. He is principally responsible for the U14-U16 teams. The focus of his work is the optimization of physical performance in the context of football. The studied sports scientist (M. A. Sportwissenschaft) is also responsible for the rehabilitation of injured players and the reintegration into team training.

LinkedIn: Joshua Skratek

- Sáez de Villarreal, E., Requena, B., & Cronin, J. B. (2012). The effects of plyometric training on sprint performance: a meta-analysis. Journal of strength and conditioning research, 26(2), 575–584.

- Seitz, L. B., Reyes, A., Tran, T. T., Saez de Villarreal, E., & Haff, G. G. (2014). Increases in lower-body strength transfer positively to sprint performance: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Sports medicine (Auckland, N.Z.), 44(12), 1693–1702.

- Nagahara, R., Mizutani, M., Matsuo, A., Kanehisa, H., & Fukunaga, T. (2018). Association of Sprint Performance With Ground Reaction Forces During Acceleration and Maximum Speed Phases in a Single Sprint. Journal of applied biomechanics, 34(2), 104–110.

- Stolen, T., Chamari, K., Castagna, C. & Wisloff, U. (2005). Physiology of Soccer. Sports Medicine, 35(6), 501–536.

- Buchheit, M., Simpson, B. M., Hader, K., & Lacome, M. (2021). Occurrences of near-to-maximal speed-running bouts in elite soccer: insights for training prescription and injury mitigation. Science & medicine in football, 5(2), 105–110.

- Opar, D. A., Williams, M. D., & Shield, A. J. (2012). Hamstring strain injuries: factors that lead to injury and re-injury. Sports medicine (Auckland, N.Z.), 42(3), 209–226.

- Ekstrand, J., Waldén, M., & Hägglund, M. (2016). Hamstring injuries have increased by 4% annually in men's professional football, since 2001: a 13-year longitudinal analysis of the UEFA Elite Club injury study. British journal sports medicine, 50(12), 731–737.

- Al Haddad, H., Simpson, B. M., Buchheit, M., Di Salvo, V., & Mendez-Villanueva, A. (2015). Peak match speed and maximum sprinting speed in young soccer players: effect of age and playing position. International journal sports physiology and performance, 10(7), 888–896.

- van den Tillaar, R., Solheim, J., & Bencke, J. (2017). COMPARISON OF HAMSTRING MUSCLE ACTIVATION DURING HIGH-SPEED RUNNING AND VARIOUS HAMSTRING STRENGTHENING EXERCISES. International journal sports physical therapy, 12(5), 718–727.

- Verheijen, R. (2020). The Original Guide to Football Coaching Theory. Football Coach Evolution BV.

- van Dyk, N., Behan, F. P., & Whiteley, R. (2019). Including the Nordic hamstring exercise in injury prevention programs prevent the rate of hamstring injuries: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 8459 athletes. British journal sports medicine, 53(21), 1362–1370.